My father’s a mechanic, a self-employed repairman of any and all things you could possibly break. What this really means is he’s an engineer at heart; life just never gave him the chance to earn the title. He’s a brilliant man, a man I’ve convinced myself could fix any car if he needed to or build any bike from scratch. When I was admitted to MIT, I cried my eyes out thinking that, of all the people I had met in my life, he was the one person who deserved to be called an engineer with a capital E. The last time I returned to MIT, there were tears in his eyes and a lump in my throat – because my father isn’t aging particularly well and I can’t be sure he’ll make it to my graduation. What greater betrayal from life than being unable to see your dream come to fruition? One of his daughters has to get a degree, and a Polaroid picture of him hangs in front of my dorm room desk as a reminder. It’s a happy picture, one where his smile actually reaches his eyes and lines trace a life’s worth of worries around them – but I don’t know why he’s smiling that way because, twenty-two hundred miles away from Brownsville, I’m trying to make his dream come true.

He’s only 56 — with wiry muscles, salt-and-pepper hair cropped short, and skin turned dark golden brown both by the days spent biking under the sun and by the assortment of oils he’s come into contact with every day for years.

He’s only 56 — with wiry muscles, salt-and-pepper hair cropped short, and skin turned dark golden brown both by the days spent biking under the sun…

He has a little beer belly and if he drinks enough it becomes a single, fully inflated lonja that withstands several jokes about when the baby is coming and whether it’s a niño or a niña. His legs are a little bowed outward, and he has a mustache that by some miracle remains mostly black. Sometimes I think that’s why he likes to drink his iced tea so much — to stain his greying whiskers dark again. It’s been more than two years since I last made some, but I still remember the recipe: two spoonfuls of unsweetened powdered tea, the juice of a whole lime, seven packs of Sweet N’ Low, and eight to ten ice cubes – but no more than that. It was always prepared in a magenta-colored cup that wound up with solidified crystals of sugar and tea in the hard-to-reach places at the bottom. Its half-life was marked by the ability to turn any water poured into it to tea – like water to wine – but my father, trained in the art of a different sort of ‘creation,’ remains a non-believer in all but the restorative power of Lipton.

My father’s meticulous approach to his drink of choice must have carried over from his work life; and really it felt like all of his life was work life. It became a running joke amongst immediate family to call him Mr. Fix It; and any time he required one of his daughters to fetch the quick-access tools under the kitchen sink, we always handed him the duct tape first. Then, a quick succession of events. A light chuckle from him. A pat on the head. A nudge towards the sink again. And then with a wrench, with a file, with a screwdriver, with a hammer, he was fixing the hinge on the folding chair, unlocking the restroom door, popping the tire back on his bike, or nailing the carpeting back down again. He fixed all of the tiny problems we could possibly encounter in the aging homes my parents could afford on $7.25 an hour. This, for a time, led me to believe that my father had gotten good at being a mechanic out of necessity. But that assessment underestimates the passion my father had for his work – it underscores his exhaustion and brings to the foreground a tiredness that screams I’m done. And when his face comes up in my mind, he is neither tired nor done – but he is definitely passionate.

During some of my younger years in Georgia, my mother worked day shifts and my father took care of my twin Karen and me. This never stopped him from getting work done and we really didn’t mind it; he would pile us into the backseat of whatever rickety old car was on hand and head around town looking for car parts or bikes to buy and customers to sell them to. I have one distinct memory of these trips around town, and the recollection of sticky leather, stuffy summer heat and the blue folding bike in the trunk transports me almost exactly to that time and that place. The heat makes the air feel almost immobile, and my sister is sitting to my right with a box of green and pink Nerds clutched in her hands. We’re parked outside of a run-down car dealership. The sound of my father bartering with a man in his Spanish staccato melts across the air until it meets my ear, muffled by the stillness. The sunshine makes everything feel golden, and I am relaxed in the certainty of a good deal for Dad, in the certainty that he will figure it out, keep us fed and keep us safe — in the certainty that he can fix anything, as the bike in the trunk could attest, if it could just talk.

But just before my mother and I gave up all hope, my father biked in through the gates of the apartment complex like an angel sent from heaven.

But my father’s impeccable ability to fix any broken thing was tested at the end of my high school career. I was late to some ceremony or other and the truck wasn’t turning on; by this point my father was no longer living in the house with us, and we lacked both the knowledge and the manpower needed to fix whatever the hell was wrong with it. I thought it was all lost and that I wouldn’t make it to school that day, which was acutely distressing considering my days at the place were numbered. But just before my mother and I gave up all hope, my father biked in through the gates of the apartment complex like an angel sent from heaven. He would of course disagree with that comparison if he were ever to hear it, but after five minutes of rummaging around under the hood of the truck, he asked us to come over and watch him stick a wooden skewer into an obscure section of the engine. My mother slipped in behind the wheel and turned the key in the ignition. The truck rumbled to life, and my father looked over at me with amusement hanging in the arch of his brow and a question resting right below his mustache – “Got it?” I hadn’t gotten it, but nodded anyway. Anything to make him proud.

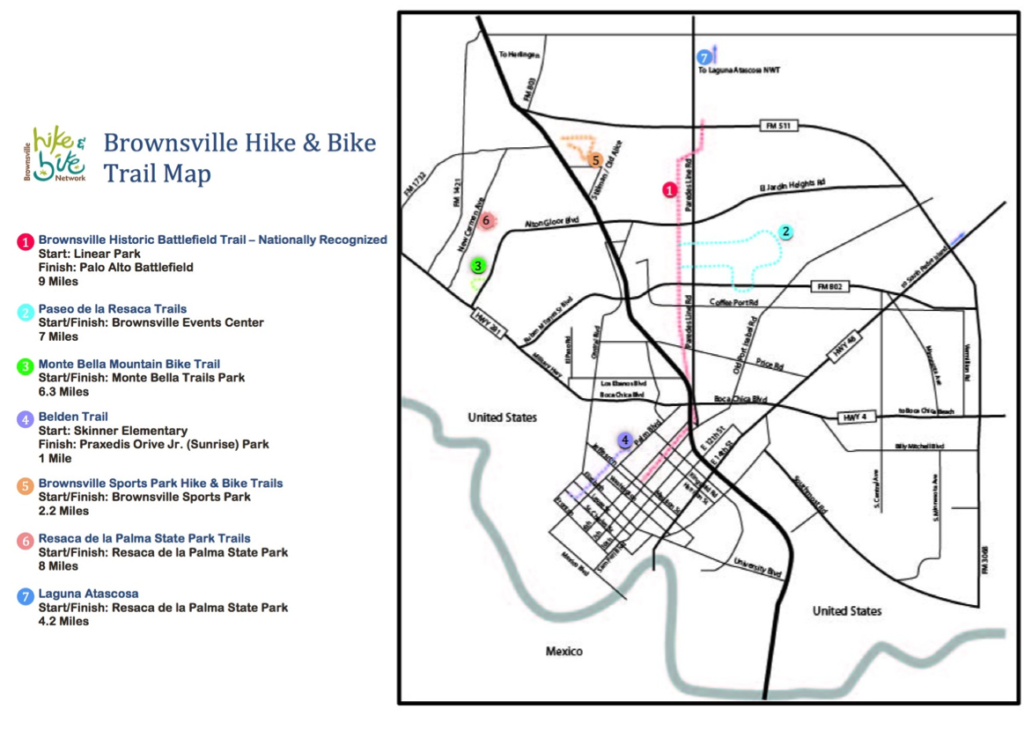

The bicycles were what insured I saw more of him than could otherwise be expected, especially after my father left home. I would be out for the evening with close friends, and we’d be cackling about some poorly told joke when I’d notice a man with a frail build on the corner of 6th and Elizabeth, presumably headed over to Belden Trail. My father. I’d be on the city bus headed home from school, and on the turn from 7th onto McDavitt, I’d note a man on a bicycle with hair just the right mix of grey and black, pedaling along the Historic Battlefield Trail. Dad. Heading back into Brownsville from a school trip on a Saturday, I’d note a man with a little beer belly pass the bus down Paredes Line Road, coming off the Paseo de la Resaca Trail. Mi papa. The biking was the reason I amassed more memories of my father than he knows. It’s the reason I cried hot and furious tears at the inequity of life on the search for the American dream. It’s the reason I made up stories about him even well into my teenage years, stories of heroic deeds involving wrenches, wire-strippers, nails and ingenuity. My sightings of him allowed me to craft a story around his life that filled the holes his absence left in it. They made him a person outside of my existence. They made him him.

My sightings of him allowed me to craft a story around his life that filled the holes his absence left in it.

But of all the ways I could remember my father, the man I remember most is from the pre-Brownsville time of our lives. This era is characterized by a naïveté that, since moving to Texas and weathering my formative teenage years, I’ve since outgrown. As I remember him, he sits on the back steps of an apartment in Georgia completely immersed in his work. Nuts and bolts are strewn around him, in the grass, amongst the dust, and on the oil-stained cement. There is order to the chaos; he knows where all things are, but asks nine-year-old me to pass the quick-release ratchet anyway. I cannot help but think that this is a test of sorts, that he wants me to learn his craft so that I can carry it with me when he is gone. I work to remember the sizes of the different wrenches, the names of the different screws — and there’s a frenzy inside of me that needs me to hurry and perfect my father’s art form. I am burdened suddenly by the weight of his knowledge pushing down on my shoulders, frightened by the idea that I must make sure his memories endure. But I am only nine in this memory and that’s probably twenty-year-old me talking – twenty-year old me, with the worry of never seeing him again.

See, my father has survived two heart attacks in his half-century of living. He battles a range of diabetic sieges: poor eyesight, extreme thirst coupled with frequent visits to the restroom, a combination of hunger and weight loss, and the bodily aches and pains that come with exhaustion. For years, I saw him prick his finger with what I later learned was a blood-glucose meter, and never thought much of it at all. Sitting quietly in the living room, peering out from behind a curtain of hair he wouldn’t allow me to cut, I’d stare at the drop of blood appearing – like magic – on the tip of his index finger. It was ritual; before heading off on his bicycle for a day of work, he’d execute the same set of movements at the head of the kitchen table. Wipe. Prick. Soak. Check. And the next day, repeat. Every morning for years – that is, until he moved out – I watched my father’s glucose meter gauge whether his body was out to get him or not.

Every morning for years – that is, until he moved out – I watched my father’s glucose meter gauge whether his body was out to get him or not.

I wasn’t present either of the times his heart failed him, but I remember coming home from elementary school the second time to an ashen-faced mother and two elder sisters with bottom lips trembling. “Tu papá tuvo un ataque del corazón,” my mother told me. Your dad had a heart attack. I was a child and the words inspired some sort of dread in me, but the severity of the situation didn’t hit until I was almost twenty and lived a life away from home. My father almost died twice, and both times I dismissed the series of events as just another trip to the hospital. They were not just trips to the hospital. They were reminders that Dad was holding delicately onto life, reminders that if he ate poorly for a few consecutive weeks his eyes would stop twinkling, reminders that the biking — while enough exercise to keep him around — could not keep him around forever. It took me a decade to realize they were reminders of the perishable nature of life. And I guess for a decade of his life my father held on because he figured one day it would hit me that he was tired and done.

When I graduated from high school, my father got to stand in front of four hundred students and a larger collection of their family members and friends. He and my mother waited right below the graduation stage, and when I finished my valediction I walked down the steps to embrace them. He was in an olive-green button-down shirt and stood with his shoulders proudly squared, his feet shoulder-width apart, his thumbs hooked on the belt loops of his dark-blue jeans. My mother got a bouquet of flowers from the principal; he got a handshake. During the ceremony, the pride I felt in graduating gave way to worrying about how he was doing. He held tears in his eyes the entire time, and never spoke a single word. I think he was trying not to cry, but I needed to know his heart was okay. I wanted the emotion of the day to be good and wholesome and not intense enough to trigger pains in his chest. I needed my father to know that reaching that milestone in my life was not symbolic of crossing any sort of finish line. It was not the time to give up, not the time to give in to the diabetes, not the time for him to go. I expected him to ride around on his bicycle for many years to come.

He had not held me in many months, maybe many years, but that night he let me wrap my arms around his chest and cry.

A few days after graduating I had a panic attack – although at the time I did not classify it as one – and because my mother had never seen me cry so violently, she called my father and told him. “Ven y ayúdame con Marcela. Está llorando.” I don’t know why she’s crying, but please come. Nothing I say is calming her down. My father biked to the apartment in five minutes, left his customary knocking at the door, and rushed in to hold me. He had not held me in many months, maybe many years, but that night he let me wrap my arms around his chest and cry. When I settled down, he asked me what it was that had upset me. Out loud to a room full of fear, I told my mother and him that I was afraid of not finding the money to eat or pay bills or send help home. But it was the last of those that struck me most, and the source of that concern was what really made me cry. At some point, my father would be gone. We’d need to find another mechanic. I’d need to help my mother pay for the expense of a plumber, the expense of a carpenter, the expense of a Mr. Fix It, because our Mr. Fix It was going soon. My mind wouldn’t stop – he’ll be gone soon what steps do I need to take to make sure we’ll be okay how do I prepare for the hole he’ll leave behind how do I say goodbye? I did not say goodbye. I have not said goodbye. We do not talk about the inevitable.

It is biking that has kept him alive, but even the biking has been dangerous. During the first semester of my sophomore year of college, I got a terrifying text message from my eldest sister – Dad was hit by a car. He had been riding along the bike lane, and some woman had not been paying attention – he insists she was on her phone. The police officer said it was his fault but did not pester him too much, and a few weeks later I was home for Christmas break. The bruises on his body were yellowing by that point, but I could tell by the way he kept his arms below a certain height that he was in pain and trying to hide it. A bruise he showed me on his leg was scabbing a little, but a few weeks’ worth of healing time should have done a much better job with the damage. I immediately thought of my grandfather, who had died before I was two because a cut on his leg had festered. I asked if he needed anything. Bandages, medicine, a phone bill to be paid. And like every other time I asked him, he told me it wasn’t necessary and that he felt fine.

He did not feel fine and he has not felt fine for quite some time.

All I wanted was for my dad to live a week. Just a week. And maybe after that, another.

A few days before I went home for Spring Break, my eldest sister Karla messaged me again. Call Dad, she said. He told mom the most heartbreaking thing yesterday. In routine fashion I asked what it was he’d said. He told Mom that whatever happens, you and Karen have to keep going. He said that no matter what happens, he wants you two to succeed. I started crying immediately – called both of my parents and both of my elder sisters – but no one answered the phone. I was twenty-two hundred miles away from my family, with four missed calls and a fear of loneliness creeping in my bones. I sat on my couch and cried because I wanted my father to make it to Spring Break. I wanted to hug him again. Scratch wanting him to see me graduate, scratch wanting to settle him into a comfortable life with the money I’d be making as a doctor or scientist. All I wanted was for my dad to live a week. Just a week. And maybe after that, another.

But now I wake up on Saturday mornings hoping my phone hasn’t rung overnight, hoping I don’t see four voicemails from four missed calls, each telling me four different ways that my father is somehow gone. All shattering the idea that this mechanic will cry when his daughter graduates as an engineer with a capital E.

Works Consulted

B.D. Diabetes Learning Center. How to test your blood glucose. B.D. Worldwide, 2017, www.bd.com/us/diabetes/blood-glucose-monitoring/how-to-test/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2017.

This is a guide that explains the different options for blood glucose testing available to individuals with diabetes. It helped me describe, with accurate and appropriate vocabulary, exactly what I saw my father do when he checked his own.

Brownsville Convention & Visitors Bureau. “Brownsville Hike & Bike Trail Map.” Brownsville Hike & Bike Trails, 2017, brownsville.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Main-Map.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr. 2017.

This PDF helped me visualize the bike trails that run through Brownsville, TX, as I was recounting the times I saw my father biking through the city by allowing me to orient and locate my memories correctly on a map.

Harvard Health Publications. The top 5 benefits of cycling. Harvard Health, August 2016, www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-top-5-benefits-of-cycling. Accessed 4 Apr. 2017.

An article on the health benefits of cycling, this source helped me convey the severity of my father’s struggle with diabetes and how cycling has helped keep him alive for so long.

WebMD. “Early Symptoms of Diabetes.” 2017 www.webmd.com/diabetes/guide/understanding-diabetes-symptoms#1. Accessed 11 Apr. 2017.

This article helped me list the symptoms my father felt as I was growing up to which I had not paid particular attention. In retrospect I remember him mentioning or doing many of these things.

289pc Mechanic’s Tool Set w/ 3-Drawer Lift-Top Chest. Craftsman, 2017, www.craftsman.com/products/craftsman-289pc-mechanics-tool-set-w-3-drawer-lift-top-chest?taxon_id=1878. Accessed 4 Apr. 2017.

This source serves as an inventory of the many tools I saw my father use over the course of my childhood.