| home |

| agenda |

| speakers |

| abstracts and papers |

| contact |

| comparative media studies |

| communications forum |

| MIT |

|

MiT3: television in transition [This copyrighted article ran in the Los Angeles Times on June 15, 2003. It is reprinted with permission of the Los Angeles Times.]

Academics say it's a legitimate discipline, but the scholar tribe lacks consensus. |

|||||||

|

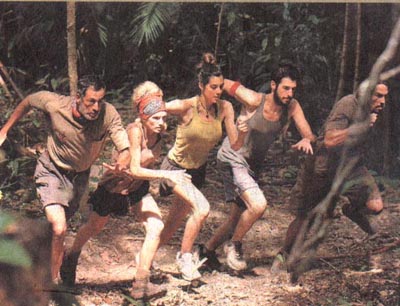

Cambridge, Mass. -- For millions of TV viewers, "Survivor" is part escapism and part game show, a chance to watch attractive, scantily clad contestants battle physically and psychologically in beautiful, contrived settings, and guess who will be voted off the island each week. Who knew that it was also about "self-reflexivity"? Or that it was a metonymy of global capital and a great case study in ignominy, or the "audiovisualization of shame," which "challenges long-held assumptions about the boundaries of genre and representation"? And just why do viewers tune in each week? Turns out it's the "mathematical processes of prediction and the narrative processes of textual pleasure" that compels the audience. Academia has tuned in to television, and it's TV's most of-the-moment shows that are garnering much of the interest, part of a broader, not universally lauded trend in cultural studies that is pushing pop culture front and center. Gone are the days when academia and television were from opposite ends of the intellectual spectrum. Instead, TV studies are now enjoying a newfound respectability and prominence in the academic world. The maturing of the medium, recording technology that has allowed previously ephemeral TV work to remain accessible in archival form, and students' comfort level with video texts rather than written ones have all come together in the last few years to give new impetus to a discipline once derided as not serious enough to merit scholarly study. It's a rich vein for study, offering a virtually unlimited terrain due to the sheer amount of TV programs on screens, something film doesn't offer. So vast is TV's purview, it offers something for everyone of every academic interest, from looking at gender roles as played out in soap operas to scholarly research into how voters are influenced by late-night comedians. As reality TV formats jump international boundaries, there's been more interest from foreign scholars and a new way to study TV's impact on global cultures. And now that TV is already more than half a century old, the medium has taken on a "historical artifact" element that some find compelling. But like the medium it studies, it's a fast-changing discipline, an "embryonic stew," says MIT professor of literature David Thorburn, one of the first U.S. academics to study television years ago. As TV studies have reached a point where they're not simply championed by a few pop-culture iconoclasts but are a staple on campuses around the country, "It's a discipline really searching for its own voice," adds Ron Simon, curator of television at the Museum of Television and Radio and a teacher at New York University and Columbia University. Ghen Maynard, the CBS executive who first championed "Survivor" at the network and now oversees it as senior vice president of alternative programming, remembers well the disdain with which his Harvard University professors only recently viewed TV. As a social psychology major, graduating in 1988, Maynard was interested in exploring the pro-social effects television could have on a culture, as opposed to the prevailing views of TV as a corrupting influence. Most of his professors just sniffed. "I was told I was just trying to justify my own viewing habits," Maynard, now 36, recalls. "Whether it was because of snobbery or elitism, they just didn't think it was worth the time." How times have changed. The first weekend in May, Maynard was back in Cambridge, Mass., home of Harvard, but he was down the street at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as one of several guest speakers at a three-day Media in Transition conference on the state of television. MIT has long been a home for scholars concerned with the effects of media on society; Ithiel de Sola Pool developed his pioneering work here on communication technology and its global social and political impact, and the MIT Media Lab is the home of cutting-edge research into the use of digital technology. But this conference, which drew some 225 scholars from around the world, had a very different tone, reflective of some of the trends in TV studies. In Maynard's session, one Cal State Fullerton academic wanted to know whether a "Big Brother" Internet rumor she had read was true. Another scholar was interested in how CBS feels about "spoilers" who try to leak or alter the results of unscripted shows. Just a few questioners challenged the concept of the shows: One complained about the cultural insensitivity of the contestants on the "Amazing Race" while another said he found "Survivor" and the like boring. While some of the approximately 115 papers presented looked at, say, how national programming affected life in rural Brazil or TV's role in the Northern Ireland conflict, a full 16 papers discussed unscripted, or reality TV. Some papers delved into reality's historical roots (a paper on "Queen for a Day" and another on the blurring of the real and the fictional in "I Love Lucy") but others looked at such shows as ABC's recent hit "The Bachelorette." The scholars were clearly well-versed in their material; at a standing-room-only session on reality TV, an obscure reference to one of the players in the first season of "Survivor" brought knowing laughter and lots of nods. It's been a fast leap from merely a decade ago, in 1992, when the University of Arizona's Mary Beth Haralovich and others decided to "have a conference about television and see if anybody shows up." They called it "Console-ing Passions" -- the topic was television and feminism -- and scholars did show up to what has now become a regular event every few years. In today's climate, even "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" has spawned its own online academic journal called www.slayage.tv and a call for papers for an upcoming "Buffy" scholarly convention lists 164 possible topics for study. DIVERSE SYLLABUS TV studies programs, in various configurations, are booming, whether they are labeled cultural studies, media or comparative communications. In recent years, the "stew" has entailed everything from courses on "Star Trek and Religion" (Indiana University) to how TV journalists worldwide cover war to links between children and TV violence. It draws from departments as diverse as anthropology, environmentalism, feminist studies, literature, philosophy, engineering and history. A lecturer is as likely to show up in a torn punk T-shirt as in a tweed jacket. Engineering school Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York started its hybrid Electronic Media, Arts and Communication program just five years ago, to provide "skills in hands-on arts design and communication combined with a broad cultural perspective," and soon had 200 students. "There's no question that when you are teaching people in a literature course, they just don't have the habit of encountering a written text in the same way as they do film or television ... where they are certainly more literate. Once they get to college, that's the way they have been wired," says June Deery, an associate professor, explaining part of the booming phenomenon. Professors too, she says, have gravitated to the topic for similar reasons, not to mention that "it's had such a profound effect on culture." The boom has generated many practical problems that must be worked out. Published papers are still the tenure-track currency at many colleges and universities, but there are few established journals devoted to TV studies, and more and more academics vying for space. New York University professor Toby Miller, who edits one such quarterly journal, Television & New Media (published by Thousand Oaks-based Sage Publications), gets two submissions a week for the 20 or so article slots each year. Underscoring the problem of the differing, sometimes conflicting rhythms of the fast-paced TV world and the more reflective academic community, one professor, who asked not to be named, recently submitted a paper on reality TV to one influential journal and was told the first opening was 2005. She withdrew the paper, fearing that by then, the references would be outdated or the genre even long dead, a victim of the hyper-speed with which programming trends blossom and die out. The growth of TV studies in the last two decades is a result of a complicated set of factors coming together, not the least of which is the pervasiveness of the medium itself. If anything, so broad- reaching are TV's tentacles, the challenge has been how to whittle it into a coherent discipline. Particularly for professors in the under-40 generation, raised in a world when television was always a force, there is an acceptance of the medium that older academics didn't share. "Very few in my generation were interested in television," says Thorburn, 62, the director of the MIT Communications Forum, organizer of the conference. The earlier generation was more interested in film. Today's students -- weaned on the work of such directors as David Lynch and Michael Mann and producers like Jerry Bruckheimer, who cross back and forth between film and TV -- no longer "have that hierarchical thinking that cinema is art and television is commercialism," says the Museum's Simon. But such distinctions were once routine, and as a result TV studies lagged for years as the stepchild of film studies departments, themselves entranced with French deconstructionist theory, which emphasized concepts such as power and simulation and ideology. The film-theory framework proved problematic for TV, says Simon. "Theory in many instances is divorced from an understanding of the historical problems of television. Television has a history very different from the cinema and other media, and you have to understand that." Eventually, film studies reached their natural limits, he says. "There's just so much you can say about the cinematic masters.... Most of it has been said. But television is still a virgin area for scholarship, and a way to bring theory up to date." As important, gender studies were gaining ground, and TV tagged along. Feminist studies focused on women's domestic spaces in the home, and from there it was a short leap to TV and soap operas, which had previously been "extremely denigrated as a form," said Haralovich, whose title at the University of Arizona is associate professor, media arts. Film, she says, was about a "patriarchal male gazing at and controlling what one sees. Television is splintered and diffuse, interrupted by commercials, and there was a realization that television as a form was maybe not inherently hierarchical, which opens the floodgates." But even as these trends converged, Thorburn thinks something else more fundamental was at work as well. "Television itself," he says, "has in a way become a historical artifact." By that, he means that broadcast television in particular is no longer U.S. society's "central medium of consensus storytelling," the way it was in the 1960s and '70s, when most households watched three channels and shared televised events that were meant to appeal to everyone across the entire population. "Television is a different phenomenon in American culture in the 21st century than in the 20th," he says. "The emergence of this television scholarship is a signal that we're emerging into a new era of television," he says, noting that the same process took place with the study of theater and the novel, both of which were once ephemeral pop culture in the English-speaking world, but not studied until they lost some of their "pop status." As Thorburn notes, none of the instructors at Oxford or Cambridge were studying Shakespeare when the Bard was writing his plays. But the move to study even the most up-to-the-minute shows also reflects an academic world increasingly comfortable with pop culture and not just the literature and theater that are now considered "high culture." "Today's high culture was very often yesterday's popular culture," says Thorburn. "Popularity is not necessarily a sign of contemptibility," he says, addressing critics who are unhappy with the whole movement to give academic status to popular entertainment. Moreover, he says, even shows that aspire to something other than high art "can be illuminating from a historical, cultural standpoint." For instance, he says it's possible such shows as FX's "The Shield" that look at the dark side of police work aren't celebrating it but illuminating it. "There's nothing that says academia has got to wait," says Horace Newcomb, another TV studies pioneer and the director of the Peabody Awards. "It was a long time before Faulkner got taught in universities and that was a mistake." So they aren't waiting, and unscripted genres have proven a bonanza. Viewers are becoming performers and the audience is becoming an active participant. For those who are interested in studies of ideology and power, it's a way to legitimize voices that previously weren't mainstream because of a "TV world dominated by men as producers and executives and desired consumers," says NYU's Miller, 44, who teaches in the university's Cinema Studies department. Reality TV is also a juicy mix of fact and fiction. "What do we mean as a culture by 'real,' "? asks Rensselaer's Deery. The London School of Economics' Nick Couldry is similarly fascinated by unscripted TV's claim to be real while it presents itself as a game. He tries to understand the shows by comparing them to ancient myths that societies used to present truths in a more accessible way. And there's a whole school of thought that says reality TV shows are merely the human experiments that social scientists would perform if their code of ethics allowed them, a real-world laboratory in which all the issues of French deconstructionist theory can be played out, says Simon. " 'Survivor' is very much about two things," says CBS' Maynard: "The effect of deprivation and the fear of rejection. Both are social issues." The emphasis on current programming is not a welcome development for purists who roll their eyes -- "couch potatodom writ large" said columnist Norah Vincent in a Village Voice article -- and complain that to study "The Bachelorette" is to trivialize academia. "Students can't even name who the president was in 1980 much less describe the details of George Washington's presidency, so given the state of American education, schools don't need to be wasting time on things students can learn for themselves" just by turning on the television, says Sara Russo, acting executive director of Washington-based Accuracy in Academia. The organization, founded in 1985, is an offshoot of media watchdog Accuracy in Media. While TV content can be an important reflection of a culture in the historical context, she says, "it's difficult to analyze in the present day in any true sense, because we don't stand outside it; we're living it." The role of a liberal arts education, she said, is to help understand the human condition, "to say something about who we are. It's possible that some modern shows do that, but it's best to let them stand the test of time." Some current TV scholarship threads are like business journalism in the go-go 1990s, which "became too much a fan, and lost its objectivity," notes Michael Keating, a media industry consultant who spent last year as a visiting scholar at MIT. Even Thorburn admits that not everyone is studying the shows with the necessary critical distance he would wish. Some, he said, "are oblivious to the disturbing moral and esthetic implications of reality TV." But Miller says if the result is scholarship that's not critical enough, the motives are nonetheless good. The old notion that "academics are above and superior to the audience" is being replaced by an attitude that "we should be of the audience, and understand its pleasures," he says. But from there, he says, it's a fine line to "sucking up to executives. Not enough of the old-fashioned public intellectual ideas are there." RESEARCH MATERIAL Other issues remain. Thorburn's syllabus has expanded over 25 years from just a handful of books and articles to include more than 40 works, including three required texts: Erik Barnouw's "Tube of Plenty," Tim Brooks and Earle Marsh's "The Complete Directory to Prime Time TV Shows" and Newcomb's "Television: The Critical View." But he says the discipline has no standard texts yet, and not enough historical research has been done. Maynard was surprised at MIT to hear quotes from some of his colleagues in the industry, taken from the entertainment trade papers and used in support of academic arguments but out of context. Despite the emphasis on current shows, the residue of its film-studies history lingers in the language with which academics talk about television. Thorburn opened the MIT conference begging the presenters to make their papers "accessible," part of his belief that ordinary citizens need to be drawn into the debates. The scholars had the sound turned down. A session on reality TV invoked the influential French theorists, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard; phrases such as the "Foucaultian gaze" and the "articulated labor of identification" and "the transformation of our surrogate from real into hyper-real" were bandied about. But Thorburn, like some others, thinks TV studies must move into something more accessible. "Foucault is a great theoretician of power. You can make the argument without the theoretical jargon," he said. Counters Miller: "If you go to some of the Web sites, some fans are using the language of French theory. Even the maker of the 'X-Files' knows deconstruction." If the discipline is to fully gel, critics say, it will have to overcome these issues and more. Thorburn is optimistic. "I believe that in the next half-century, the television of the second half of the 20th century will be an increasingly central topic of study. We're only seeing the beginnings now." sidebar:

|

A

stab at equality

A

stab at equality

The

agony of defeat

The

agony of defeat